Episode 3

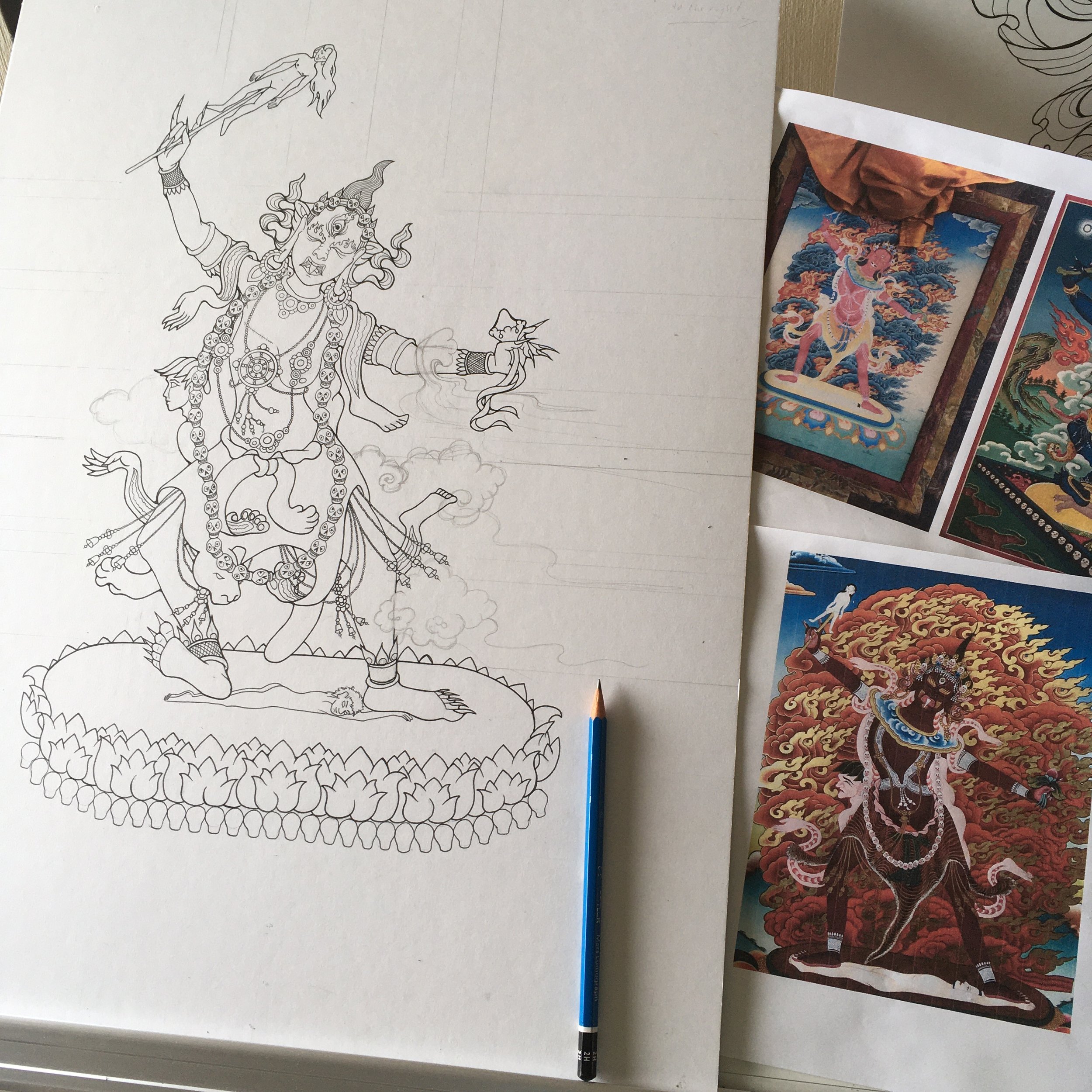

Manjushri Thangka in progress

Kaitlyn Hatch

Queering Buddhist Art: Drawing a Path to Inclusivity

“Any system of oppression can't be part of the sacred because it's a perversion of the sacred. Because systems of oppression create the idea that some people are more sacred than others, and that's wrong. … Therefore, I have work to do all the time about being aware of how I believe those messages, and how they are constantly bombarding me, and trying to convince me of their rightness. What am I always doing to bring awareness to them, to be present with them, to acknowledge what is my responsibility versus what is the system and how within the system can I push against it at all times? And then what are the areas where I can just model that sacredness that a system like cisheteronormativity, for example, doesn't believe is sacred.”

- Kaitlyn Hatch

"How do I show up to protect what I love, which is the sacredness of every single precious human being?" - Kaitlyn Hatch

Kait Hatch is a multi-genre writer, mixed-media artist, Buddhist chaplain, philosopher, and community organizer, whose unique identity as a queer, disabled, racialized white Canadian with Métis, British and French colonialist ancestry informs their worldview and work.

In this episode, we explore how art, contemplative practice, and social justice intersect and inform Kait’s work creating contemporary Thangka pieces depicting Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in all different embodiments resisting dominant gender and cultural norms, and the Sacred Love/Sacred Lives mixed-media series celebrating disabled, trans, and queer folks.

Footnotes/resources:

Learn more about Kaitlyn Hatch's work, her Sacred Love/Sacred Lives project, and her Representation Matters series

Find out more about the process of Thangka painting

Learn more about the Thousand Armed Avalokiteshvara and Manjushri

Read Pema Chodron’s essay on practicing peace or this piece on how lojong (mind training) awakens the heart

Listen to Zenju Earthlyn Manuel discuss The Way of Tenderness: Awakening Through Race, Sexuality and Gender

Sacred Love/Sacred Lives:

Mixed-medium embroidery pieces celebrating the sacredness of disabled, trans, and queer folks

GUEST - KAITLYN HATCH

Kait is multi-genre writer, mixed-media artist, Buddhist chaplain, philosopher, and community organizer. She has self-published two books: Wise At Any Age: A Handbook for Cultivating Wisdom in 2013, and Friends We Haven’t Met Yet in 2016. Her long-running blog includes the Lojong Practice Journal, a reflection on the 59 Lojong slogans through the lens of social justice.

Kait’s work has also been published in Huffpost, elephant journal, and Lion’s Roar. She has written a half dozen manuscripts inspired by her longing to see more stories that reflect the neurodivergent, queer, mad people she knows, loves and is also one of.

A love for androgyny and gender-play led Kait to found Fake Mustache, the longest-running drag troupe in Canada, in 2005. Kait also founded the Miscellaneous Youth Network, dedicated to creating safe spaces for QILT2BAG+ youth in his hometown of Calgary, Alberta.

As a Buddhist Chaplain, she offers spiritual support and guidance for white, cis gender, and abled people of any sexual orientation who want to effectively disrupt and dismantle systemic racism, white supremacy, cisheteropatriarchy, and ableism. Kait’s work is grounded in their own practice of anti-racism & Disability Justice, their Buddhist practice of over a decade, and their training in the Upaya Zen Center's Buddhist Chaplaincy program.

-

-

Desiree (00:34.537)

I'm just really excited to be in this conversation with you. So if I could just dive right in with a question here for you.

Kait (01:17.63)

Let’s do it. Go for it.

Desiree (01:20.457)

You've mentioned or I've read about how you created art as a child and you would get some inspiration looking through art books that were in your home. And once I saw that the first question that came up was, what was it like growing up for you in terms of creativity? It sounds like there were at least some pieces of it there. How was it? Was it a place where creativity was cultivated and valued?

Kait (01:59.294)

Yeah, absolutely. This is such a good question. I love this question. This is a question I would prefer people ask me instead of what do you do? Tell me about the creativity of your childhood. Both my parents are artists in their own way. It's funny because growing up, my mom always said that she wasn't an artist. What my mom meant by that is she doesn't draw. But my mom does ceramics. She taught me how to do an eye. She taught me how to make an eye look like an eye. So, she's very good at how to get the light glinting off of it and get the proportions correct and all of that. So it's funny when she was like, I'm not an artist. She's also a quilter. She's a scrapbooker. She has a really good eye for composition and she can do the mathematical art. She's so good at quilting because she likes math.

And my dad was a photographer. He's a baker. And I think the way that my dad bakes his art. He makes model airplanes and he does woodworking. So I grew up in a household where there was lots of furniture that my dad had made. And he spent time designing it. He also made wonderful wooden boxes for people of all different kinds, like jewelry boxes and boxes for knickknacks and stuff, and he got quite into it. And then drawing was hugely encouraged. My household was a very creative one. We didn't have a television till I was 12. So my life was full of art and books and board games, card games. Lots of creativity and a lot of encouragement to have fun with it. One time my parents were going to re-wallpaper one of the walls in our house and they got us as the kids to help with the destruction and ripping it all down. And what it exposed was this pale green papery surface. And we knew that we weren't going to be able to do the wallpapering until after Christmas.

So in the lead-up to Christmas, my parents gave us whatever supplies we wanted and we and our friends could draw all over the wall. And we did this massive motif of Christmas decorations. Like my brother painted a giant chimney and I put a cat on it and a dragon because I put dragons everywhere. It was encouraged when I was a kid.

Desiree (04:46.045)

Yeah, it sounds like you were surrounded by it.

Kait (04:48.99)

Absolutely, yeah. And it's funny because as I got older and people would ask me, I would repeat what my mom said. My dad's an artist, but my mom is not. And then I started to recognize that art is not just drawing, which I always knew. I also sculpted a lot as a kid. I learned that actually from my aunt. She taught me sculpture with polymer clay. It was when I was working with sculpture that I started to think about how my mom's work with ceramics and being like, wait, that's art.

Desiree (05:21.669)

Absolutely. So, it's been there. It was cultivated. You were surrounded by it. Is that something that was a part of what you continue to work on and practice as you grow older? Or was it something that you put down and returned to later on?

Kait (05:45.626)

No, there's never been a time when I wasn't doing art. I think my relationship to it has changed and my identity around it has changed because when I was a kid it was like, yeah, that's what kids do. We do art. And then in high school, getting to work with a lot of different mediums, I think I was trying to figure out what's my medium. And so then I got stuck on acrylics for a long time, which was fine. But I think what happened for me, my evolution was that I still thought that being an artist was being one kind of artist. It's been pretty recent that I was like, wait, all the mediums, I like them all.

Desiree (06:28.925)

And it's all art.

Kait (06:31.062)

And it's all art.

Desiree (06:32.821)

Amazing. So let's dig in a little bit more into that. Before we weave some threads together, another part of your bio and experience has been the contemplative practice, the path to Buddhism. And I'm curious what drew you to that path. I know that's probably not a short answer and I love it.

Kait (07:14.574)

It is and it isn't. What drew me to the path was I was seeing a psychologist, she was teaching me meditation, she kept on talking about Buddhism, she kept on recommending this author Pema Chodron to me and was like, “You should go read some of her books.” Because a lot of the stuff you say, she would say like, “I think she'd resonate with you. I think her way of writing would make a lot of sense to you.”

And I finally got around to getting a Pema book and I read it and it was instantaneous. I was like, oh, I'm a Buddhist. It didn't feel so much as I became a Buddhist as I realized I always was. There was just something in the framework that clicked and made sense to me. I was like, oh yes, interconnectedness. I know this. This is what I was raised on. A sense of belonging within a web of things.

That was a big part of my upbringing as well. And that came largely from my mom, who is Métis, and something that she learned from her grandmother. And it made a lot of sense. I was like, everything about Buddhism makes a lot of sense to me. It's about being within the body. It's about seeing ourselves as part of nature rather than separate from it. It's about having a sense that what we have is what we need. We can work with it all right here. You don't have to get anywhere. So I was like, ah, yes, perfect. Brilliant. I found the thing.

Desiree (08:52.413)

Yeah, and when was that? When was the picking up of the first Pema book?

Kait (08:59.278)

It was in 2008. I can't remember exactly when in 2008, but it was in 2008 and I will say that I got obsessed real fast. I went hyper-focused like, yes I'm going to read everything this person has ever written.

Desiree (09:15.761)

Which is a lot.

Kait (09:17.77)

Yeah, that is a lot. It was a good job that she'd written so much because I think it gave me at least five years of reading.

Desiree (09:25.745)

Oh wow, really deep dive.

Kait (09:27.874)

Deep dive. Yeah, and that's me saying also, like, I've reread most of these books multiple times as well.

Desiree (09:35.842)

You mentioned that it didn't land. It just felt like, oh, this was already here. This is resonating with me. And that you felt like that was something that you'd already been brought up with. And I just want to ask about that a little bit more in terms of what that feeling was or how that was cultivated, at least in your home.

Kait (10:12.198)

Oh, well, this is one of those weird things because you've got your childhood and as a kid, there are just certain moments when you realize not everyone else's family is exactly like yours. It's a very universal experience of you go to someone's house and you're like, “Wow, you do this so differently.” This is weird. I was fortunate in the experience that I had growing up in the neighborhood I grew up in. I grew up in an inner-city neighborhood, but I didn't know it was inner-city because it has very small-town vibes. Everybody knew everybody. Everybody looked out for everybody. And a lot of people had similar worldviews to my family. So it just was normal for me to have a relationship with the land.

I'll say that was just really normal growing up in this neighborhood. The elementary school I went to was a green school. It was the first green school in the city. So everything about the school, culture, and stuff was focused on understanding the environment around us. There's some reclaimed space in my neighborhood that used to be an oil refinery and it got cleaned up. And when I was a kid, a big part of our school curriculum was going over there and planting trees and also just spending some time there and getting instruction on what are the local animals. And again, when I say I grew up in an inner-city neighborhood and didn't know that and people are like, “Yeah, you think you had a small-town experience.” I'm like, no, what I mean is I grew up in a place where deer would walk down the road and if your pet went missing, it's because coyotes ate it and porcupines would come into our yard to raid our raspberry. There's wildlife abundantly around here.

And I never was taught or believed for one second that their lives weren't as precious as mine. I never saw any animals as a pest or a nuisance or they didn't belong or shouldn't be in the environment just as much as me. And also growing up with the friends that I had in the neighborhood in the summer, we were just roving around like little packs of feral children basically, interacting with that environment all the time and having this sense of deep belonging in the environment. My childhood, when I think of my summer memories, is running through fields and along the riverbank playing games and finding grasshoppers and making little grasshopper habitats and setting them free at the end of the day.

And being able to recognize bird calls and know what different kinds of birds are in the neighborhood. So all of that is just part of it. And I had a childhood where I was really in my body. I'm one of those very fortunate, rare cases where my parents started to try and do something about intergenerational trauma before it came to me. So, my mom was trying to fix some of the things that in her childhood had been so bad and not carry those forward. One of the big things for my mom was making sure that both my brother and I had a really good sense that our bodies were ours and to listen to them and trust them and know how to ask for what we need and recognize what our body is asking for. I had a good somatic relationship as well growing up. My experience more so is like as an adult going out and being like, oh wow, that's not usual.

Desiree (14:01.913)

No, and I'm struck by not just what you mentioned of having that connection and being attuned with nature and the land and what's happening around you, but that you did have, even though you wouldn't have named it this way then, but that real connection and attunement to what was happening and that your mom was able to cultivate that or be present with that and to offer that space for that is incredible. That practice of just being present and attuning sounds like it's been there for a long time for you.

Kait (14:45.554)

Yeah, and I think most of what happened was I had a serious disconnect through my experience in junior high where I was bullied. I was not the right girl because I was performing gender incorrectly. I knew that I wasn't straight, but I still didn't have language. I got this sense of mistrust that I wasn't okay. It's really hard. I think about my childhood being almost like a utopia, and it was great. But three years of just relentlessly being told that you are wrong damages the psyche. I stopped trusting my okayness through that experience. And it didn't help. I say this to people all the time when the message that I got predominantly from adults was to just ignore people as if I could ignore the people I had to be at school with for seven, eight hours a day, five days a week. Or just try to change yourself, change yourself and they'll stop bullying you. I never saw anyone hold anyone accountable for the way that they treated me. I just saw that it was my responsibility to make sure that they didn't treat me that way or that I didn't let it get to me, which when you're 13 and 14 and feel like you're a child and you're being told your peers are right actually. You do need to change and you aren't good and you're not okay the way you are.

Desiree (16:28.077)

Right. It's like incorrectly placing the pathology on you instead of the social context.

Kait (16:35.306)

Right. And it's still a persistent problem. I would say that the other thing about Buddhism just fitting and making sense was again hearing a message that even the things that you think are messed up about yourself, even that is ground for you to work with, even that is something for you. So, it meant that there was nothing I had to slice off or separate or put elsewhere. It was like, all of me is okay and all of me can be here in this situation.

Desiree (17:08.027)

And all of it is a ground to yeah work with and learn from. Sometimes frustratingly.

Kait (17:19.226)

Well, I will say, that another really interesting experience for me with Buddhism was that it took away the frustration about a lot of stuff. So I was like, oh, this is something I can work with. It doesn't have to be something I have to get rid of. It's useful.

Desiree (17:33.949)

It's useful. I remember Roshi Joan (Halifax) once in response to a question I had. I don't remember the question now, but the response was, “Yeah, you’ve just got to work it.” Just this utter acceptance and that's what we have before us to be in and to move through and to transform, make something out of, make art out of.

Kait (18:09.906)

Yeah, absolutely. Exactly.

Desiree (18:12.689)

This leads me to another question. Which came first? The path to the Buddhist chaplaincy or the thangka art?

Kait (18:31.318)

Oh, the art.

Desiree (19:21.173)

The art came first. What brought you to that art? I know you mentioned painting and everything before, but was there something specific, a moment?

Kait (19:23.885)

Okay, so this is a great question. I love this because I've been sitting with this a lot lately. The first thing, I'd say there are a few origin points. I think the first thing was that I was always a little bit wary of doing cultural appropriation effectively. As a Buddhist, I am a deep practitioner and I'm aware that I'm practicing. Most of my lineage is in the Nyingmapa and Kagyupa schools and Tibetan Buddhism. But in North America, you got a mixed bag. It's all there. So, I'm always really cautious from am I just appropriating something from an Asian culture and then performing that. Or is this Buddhist practice? Is this Dharma? Or I'm performing Japanese-ness or I'm performing Tibetan-ness or whatever. And so I was a little wary whenever I would see a thangka. I would be like, that's nice, but that's someone else's culture, and I'm not gonna muck with it. And then I got a book that was called Meeting the Bodhisattvas. And this was mostly because I'd heard a talk that was about Bodhisattvas and I was like, oh, this whole concept of Bodhisattvas. Sounds interesting. I want to understand it better. And I didn't know that often the art I was seeing was of course depictions of Bodhisattvas. So I opened it up and I'm like, oh, that's what these are.

This was very early on. I started meditating in 2008 and it was probably about 2010 that I started to get curious. And it was in 2012 when I got this book and I was flipping through it and I got to Manjushri and I saw Manjushri.

Desiree (21:37.501)

Yep. I mean that sword.

Kait (21:42.478)

That sword. Also, this figure is extremely beautiful and genderless. This is just like this beautiful genderqueer person wielding a flaming sword.

Desiree (21:43.494)

Oh yes, and for those who will be listening, who may have zero idea of what we're talking about, would you just briefly describe the meaning of the sword and the image?

Kait (22:15.122)

This was the thing because I didn't learn the imagery for a long time. I just know that I saw this fiction, it was compelling. And then once I started to study Bodhisattvas more and learn stories, the thing about Manjushri is Manjushri's sword is just cutting through. Manjushri's sword is like, you think you know something? You don't know. You think you know now because you thought you didn't know that? No, you still don't know.

Desiree (22:19.415)

Yep, let me slice through that a little bit more.

Kait (22:43.478)

The description of the sword in sutras is it's a diamond blade wrapped in a cold flame. There's no ignorance that Manjushri can't cut through. And then the stories of Manjushri, like one of my favorites is from the Vimalakirti Sutra, where Vimalakirti is sick and the Buddha is asking all these people, like how come no one's gonna visit Vimalakirti in his sick bed? And all these different great lords and whatever, they're all like, the last time I saw Vimalakirti, he schooled me. So, I don't want to go see him because like he makes me realize that I'm not really as realized I'd like to be. And then Manjushri stands up and is like, Vimalakirti also schooled me and it was good for my practice, so I'll go see him. And I'm like, that's how I am. It makes me weird, I realize that I'm like, oh, this is uncomfortable - I'm going to dig into it. I want more of it. I want to keep cutting through the ignorance again and again and again. That was the first image that I felt some connection with even before I'd learned any of this, or done any of this study. The point of these pieces is that they are such a powerful image that it speaks to something in the practitioner. And not all of them will speak to every practitioner, but the right image just does something. After that, I got curious about thangkas and I started to look into it. And I reached out to, at the time I lived in London in the UK, and I reached out to someone about possibly getting lessons. It was through a community at the time that I was participating in quite a bit.

And then I found out that their founder had done lots of sexual abuse. So, I left. So that connection was gone. But then the other thing is, I find it funny when people equate learning to something you can only do in an academic or school setting or with a teacher. I am my own greatest teacher. I love teaching myself stuff. If I'm curious about something, I'll go and I'll learn it.

I just started to look at the small, different objects in these pictures and draw them for fun. I'm gonna try and see what happens. Especially things that I liked. Like if you look at a peony in a thangka drawing, I love peonies, and I'm like a peony in a thangka drawing. They're gorgeous, I wanna draw them. Another thing is, in my art, I love detail.

So one of those art books that I grew up with, is MC Escher. MC Escher books are all over my house. I love the detail. And I never had the patience for it. So what would happen with my artwork is I would have something in my head and I'd wanna get it done. So I would simplify it until it was finished. And I just rushed through it. But with these pieces, even just doing the tiniest details, I was like, no, you can't rush this. Then I met my wife and she bought me a book. It's the only English resource you can get on how to draw thangkas. She bought it for me and it has the practice. And I was like, oh, this is a practice. There's a whole grid and understanding the grid is understanding the form you take when you go to meditate. How do you hold your body?

Like, how do you prep your material? How are you going to be present with it? Understanding that what you're creating here is sacred and hopefully for the right person, a glimpse into that Buddha nature that we all have. So that was when I started to move into figures because I was like, oh, now I've got a grid.

And that would have been about 2014, or 2015 that I started moving into drawing figures.

Desiree (27:08.465)

It's been quite a few years since that. And now you're working on something not tiny.

Kait (27:13.23)

Not tiny at all.

Desiree (27:24.765)

Can you tell me how that came to be if that's part of the story that you would like to share, and what it is unfolding to be?

Kait (27:39.478)

Yeah. At the end of 2022, I finished my first color thangkas. I've done several figures and I've always just stuck to line drawings and most of that was because I was still really understanding this craft and understanding this particular medium. It never felt right to color them. I don't know, I just wasn't there yet. Over two years, I drew the five Buddha families. So the five Buddha families represent the five Buddha realms. And I drew them in non-male form because basically, people are always talking about how all the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas have attained rainbow bodies so they can show up in whatever form they want. So as far as I'm concerned, they're all beyond even a binary anything, like they're ultimate non-binary beings.

Desiree (28:46.565)

You're just expressing what it says.

Kait (28:49.074)

Exactly. I was like, I'm going to draw the five Buddhas in non-male form. And I finished that. Then I was like, I think I want to color them now. But I didn't want to color the line drawings I'd done. So I had them imaged and then I had them blown up and printed in soft gray. So the outline was just a soft gray so that I could just color onto that. And then another two years, I spent creating these colorful versions. And this was where my mixed media thing came in. These pieces are acrylic pencil crayon, which is colored pencil for everyone who's not Canadian. They're called pencil crayons in Canada. Different kinds of ink pens and also washi paper, which was fun. I cut their robes out of washi paper. I finished them towards the end of 2022 and I did a little presale to sell card sets for folks I wrote a little thing about practicing with each of them and what this practice had been and just reached out to my little Buddhist network and was like, here you go if anyone wants these cards. One of my connections through Buddhist chaplaincy forwarded it on to a Buddhist chaplain at Davidson College who bought a set and then filled in my commission form on my website, which was wild and exciting because that's never happened before. And he was like, “I like your work and I am this chaplain on staff and I'm able to get some funds to pay an artist and I'd like to commission you if you'd be interested.” And I was like, “I am interested. Let us discuss.” He presented two options. He was like, do you want to do the Wheel of Life or do you want to do the Thousand-Armed Avalokiteśvara?

I was like, “Oh, I thought about doing both of those many times.” And they're both complicated. They're very elaborate pieces. Like one, you've got this incredible mandala that's everything. It's life. And then you have a thousand armed Avalokiteśvara. And.

I met with him. He's lovely, we had a chat. Avalokiteśvara is the deity that he practices with the most and has the strongest relationship and I was like, “You know what? Let's do it. Hands, the most challenging things to draw, I'll do a thousand of them, sounds fun.” It was great because when we met, it was like we had a good open honest conversation. It's one of those things that I'm always navigating around this artwork I don't want to see it corrupted by capitalism. Very anti-capitalist. This is a sacred art. This is practice art. I have a deep relationship with it. I don't want it to be exploited. At the same time, we're talking about a lot of supplies a lot of research, and a lot of hours of labor and skill. It's like a balancing act. We live under capitalism, so we have to survive. But it was great because I just opened with that and even was like, oh yeah, totally, it needs to be a balance of like, you have to get paid and this is also a practice too. So, we don't want to have that pressure of a deadline.

I will say, that the greatest gift that thangkas have given me is patience. Like I can't even begin to tell you how impatient of a person I usually am. But with thangkas, I'm just like, no, it'll happen when it happens. No rushing it.

Desiree (33:01.213)

No rush, no deadline. What a gift.

Kait (33:19.542)

Yeah, I told him, “I could do it in a year.” And he's like, “Okay, I'll give you two.” And we're practicing together around it. So it's really lovely because I've got this relationship with him where we meet regularly and he shares things he's learning, sutras he's come across, or practices like chants and stuff. And then I tell him about like, things I've learned about imagery. Like I'll say, I feel like I'm able to do this now because I did those five Buddhas. The five Buddhas are like the core. It's the multiverse of Buddhism. I've got it now. There's so much of the relationships between all the different Bodhisattvas and the way they show up in people and our lives and practices that if you understand the five Buddhas, you can get acquainted with any of them now.

Desiree (34:01.717)

You've spent some time with them.

Kait (34:21.354)

Yeah.

Desiree (35:04.517)

You mentioned previously that you were looking to explore both the lineage of Buddhism across cultures and also the lineage of liberation movements, and then also this question of when are all the hands? That sounds like so much to hold, even as I'm saying that out loud. I'm just curious. As you've started this, what has this experience been like to have this practice that you know is going to take the time that it's going to take? How are you holding, swirling with these, intentions you have about it? Are they staying with you as you're sitting with it or is something else happening? It seems like a foggy question now, but that's all part and parcel of what's arising in me as I'm thinking about what you're doing here.

Kait (36:05.273)

Yeah, I don't think it's that foggy. That's a lot. How are you managing all of that? Well, let's just say a thousand hands helps.

I was speaking with my wife about it when I was like, yeah, this whole idea of like, I want to get the sense. Because Avalokiteśvara, you have this initial deity that came out of what we currently know as India, but traces back to a time when it wouldn't be recognizable to us now what was there, and moved into Tibet, and then moved into China, Vietnam, Thailand, Japan, and Korea. And everywhere this figure moved, it was adopted and then absorbed things about the culture. The depictions vary so much and they're also rich. Again this is one of those things of how I work with whiteness am I ensuring that I'm doing something that

honors that I know where this came from? This isn't mine. This is something that has been handed down by so many artists all over. I will say one of the most amazing experiences of that for me was with this grid. There are all these different grids for all of the different bodhisattvas. And I will say it was a quest to get the Avalokiteśvara grid for a thousand arms.

Desiree (38:00.605)

How large is the piece?

Kait (38:04.066)

I measured it the other day. It's 27 inches by 42 inches. It's pretty good. It's a decent size. The idea with the grid is that depending on the deity, there's a universality to the form that they take. So if it's a seated Buddha, they all have these proportions. If you've been trained in art, where you can draw your standard human, but then you also have heroic proportions, that's what this is. And the thing is, I have loads of grids.

And I thought, oh, right. Standing Bodhisattva, that's what this is. But no, of course, it isn't because it's the thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara. So they have their special grid. Yeah. A dear friend of mine, one of my fellow chaplains in my cohort, when I let her know that I was working on this, or getting ready to be working on this, she was like, “Oh, do you have Robert Beer's book?” Robert Beer is an English expert on Tibetan artwork. So he has an encyclopedia of Tibetan symbols and motifs. And she said, “I'll send it to you as a gift.” And I was like, “Oh, that's sweet of you.” And then when it arrived, she threw in this other book called The Art of Awakening, which is effectively a compilation of all of the practice instructions around doing thangka practice.

And guess what's in the back of it? The thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara grid.

Desiree (40:01.405)

Exactly what you needed.

Kait (40:07.83)

Exactly what I needed. I get the grid and I can figure out what the proportions are. It's a scalable thing. I figure out what the proportions are, I sketch out my grid, and then I sketch out just the lightest figure. For this project, I got a digital projector. Hopefully, this will make drawing a thousand hands a little bit easier. After I got the grid set, I set up the digital projector and I've got all these other pieces that I've been looking at from all these different cultures. I started projecting them up on what I had drawn and they all fit the same grid. And they'll look completely different and they also fit the same grid. For anyone who's ever drawn a lineage chart where it's like, here's the Buddha, that was my lineage chart moment. Like that was me. I was like, I am the next in a line of countless beings who came before and countless beings who will come after to draw this particular Bodhisattva. How do I honor that? Presently, I'm honoring it all the time. I talked to my wife about it. I was like, is it going to be too much to try and incorporate all the different cultural contemporary social movements for liberation? And then I was like, but it's a thousand arms. How could it ever be too much?

Desiree (41:47.541)

Thousand arms. It's so many arms. And it's not metaphorical, you have to draw them all.

Kait (41:51.854)

Yeah., I've prepped 32. I have the next 72 ready to go for the first array out of the outside. I figured out the scaling.

Desiree (42:07.165)

Amazing. Let me pause on gushing about that. I read something you'd written that said, I want so much to see a representation in Buddhism that I so often don't. As I've been learning about your work and seeing what you have already been creating that looks different than what you've seen and what you're in the process of creating, I'm curious what that has been like for you to bring some of this out from what you had been wanting internally and now bringing it outside beyond yourself and having it exist.

Kait (43:54.03)

Here's the other thing that's been interesting about this experience, and is true of most of the thangkas I have drawn up to this point, but particularly true of this one, is I don't even feel like I am creating it. It's just revealing itself to me. So much of that is because I'm aware as a queer person when I'm studying a sutra or something, I'm studying some dharma there's just an inherent queerness to it. It is very queer. Then you look at the artwork and think, okay, so this artwork is almost all created by monks. And that's fine. And we're also talking about patriarchy baked into everything.

It always has been. And that shows a lot sometimes. So, I think it's almost impossible. For anybody, if you are a Buddhist, if this is your path and you don't see yourself reflected in the deities that you see, that's not you. That's not your fault.

That's not your problem. That's because art is so often, it is a reflection of ourselves. That is what we put out into the world based on our experiences and our understanding. I don't feel like I'm creating something that shouldn't already exist and shouldn't already be obvious. That very first Manjushri I saw, was genderqueer as heck.

There are a lot of different depictions and they aren't always so gender queer as the one that I first saw. And that matters. I don't know who drew that one. It's not credited to anybody. It's just a line drawing in a book. All I know is that when I saw it, I was able to see something of myself in that and something of my potential. And that is what these pieces are about. I think that's another thing that I'm loving and I'm so grateful to my dear friend for sending me this Art of Awakening book. I text her regularly where I'm like, “You're the best, you're so great. You have no idea how much this is helping.” I just read a passage in it that is about doing deity practice and the importance of picturing yourself as these bodhisattvas. But it's really clear in this passage where they're like, remember you're not picturing yourself as the bodhisattva, you already are the bodhisattva.

And that's the other thing I'm so aware of. As I'm drawing this, I'm thinking I am already this being. And I'm thinking everyone who looks at this, I want them to think that's me. And that is the responsibility that you have as the artist when you're making this art. It's like who is it that's going to look at it? I've got the most gender-queer figure going on. I love my Avalokiteśvaras.

And their face just revealed itself to me and I was like, ooh, high femme energy. I love this. That's the thing like, I am this being and so is everyone who looks at this being and I want them to be able to see themselves reflected. Does that answer it? I think.

Desiree (47:48.773)

It does. And it's so clear what you'd like to offer with it. I'm just thinking about my own experience in Buddhist spaces and the images I see. It's not a small thing to offer either an image or a space where someone feels drawn to the Dharma path or the contemplative path for those who are not on the Dharma path.

But to find something of themselves reflected in the space or the images. So yes, there's a sense of connection or belonging at best. And on the flip side of that, that someone doesn't have that feeling of, I thought I wanted to be here, but maybe this isn't the space for me. And so, I just love that you're creating these images and you're engaging in this practice and that representation is such an important piece of your work. I also wrote down and read what you said, it just seems like activism and challenging tradition is a thread that's woven into.

near multiple projects. I just wanted you to speak on that more, if that's been intentional for you for a long time. I'd just like to hear more about that.

Kait (49:55.95)

My mom did a good job. My mom taught me from an early age to be super sus about authority. For me, it's looking at things like, I think I can give you a really solid example of listening to a talk and a woman, asking the teacher about the fact that it is patriarchal and all of these images are of men and she doesn't see herself reflected. And the teacher said, “Well, don't like to throw out the baby with the bath water. Find a way to make it work because the teachings are really good. To me, that just smacks me as a teenager being told, that if you just try to fit in better, maybe people wouldn't bully you. It fundamentally misses the reality of what we're living in. And this is another thing that I love about Buddhism is the marriage and relationship between the relative and the ultimate.

So the relative experience is the only experience that we can work with because that's what we each have, we have a relative experience. And the ultimate experience is the interconnectedness of every single relative experience. It's not that it's real or not real, there is an actual impact there. I am fiercely dedicated to justice and liberation and I want liberation for all beings. I'm just gonna collect my thoughts here for a moment. I get so passionate about it. At the same time, also frustrated sometimes. I think it would come back to teachings by Zenju Earthlyn Manuel, who is one of the most gifted living Dharma teachers we have right now. And so she has in her book, The Way of Tenderness, which I cannot recommend enough. If every single being on the planet read it, that would be great. It's my number one book. I recommend it to all beings. She has a whole section and she has this line that there's multiplicity in oneness. And it's a real mistake that people get into where they hear oneness.

Or they hear the ultimate and then they fall on that as if oneness is sameness and as if the ultimate matters more than the relative. The whole point of this practice is to move beyond that dualism and not see it that way. A friend and I have been having a little bit of a discussion about the sacred because of this whole thing that I read about, you are already the Bodhisattva. Like you are a sacred being. I was saying how any system of oppression can't be part of the sacred because it's a perversion of the sacred. Because systems of oppression create the idea that some people are more sacred than others, and that's wrong. That's why I'm always aware like, okay, I have been conditioned and raised within a society in which whiteness is held up as superior, better, more important, and more valued. I fundamentally disagree because all beings are sacred. Therefore, I have work to do all the time about being aware of how I believe those messages, and how they are constantly bombarding me, and trying to convince me of their rightness. And so, what am I always doing to bring awareness to them, to be present with them, to acknowledge what is my responsibility versus what is the system and how within the system can I push against it at all times? And then what are the areas where I can just model that sacredness that a system like cisheteronormativity, for example, doesn't believe is sacred? It's like trans lives are sacred. We need to protect trans people. Anybody who is attacking the fundamental existence in the humanity of anyone else is attacking the sacred. And therefore also harming themselves. That's the other thing. That's where I can keep that big compassionate heart. Whereas you do have Buddha nature and I'd rather you lean into your Buddha nature because Buddhas aren't fascists. Does that answer the question?

Desiree (55:00.829)

I think it answered what we needed. Let me gather myself now and look through it. Essentially what you're sharing with me of being in this constant practice of what am I doing? What am I modeling? What is mine? What is not mine and I should put down? This constant awareness, it's just highlighting for me the amount of effort this takes. It's pointing me towards another thing that I read that you've talked about, or at least mentioned about the protector principle, and is one of accountability and how we can't wish for equity and for justice that we have to effortfully obtain it.

And it seems like you have been in that practice. And so, another thing that I'm curious about now and I don't know how you'll answer this, but the process of your creative practice, your engaging in the thangka art, how does that touch your Buddhist chaplain work, your consulting work or the workout in the field?

Kait (57:01.202)

Yeah. It always does. Working on a thangka is building a relationship. It's weird to explain it to people who aren't Buddhists because, on the one hand, this is a visual representation of our wisdom. It is our own Buddha nature and it might just be an aspect of it. Like Manjushri, the aspect of cutting through ignorance. The protector ones, Dakini in particular, are always very fun, but also Mahākāla. They're definitely about accountability. You can't cut corners with the practice. You can't do the practice in a way that makes you comfortable. That's not what it's here for.

You aren't going to get comfortable in Saṃsāras. Saṃsāras are not comfortable. That's the point. They're like, me being able to recognize that in myself, but they're also there. I'm like, ooh, like, and Dakini is watching me.

Am I doing the right thing here? Am I paying attention? Am I being honest with myself? Because I don't want her to show up in my dreams. It might be very uncomfortable. However, she's going to show up. So, it is always present, even if I don't necessarily talk about it with the people that I'm interacting with.

It's saying, when are all the hands? It's also sort of like, who are all the hands? What actions are all of the hands doing at any given moment? What are the things of body, speech, and mind that I can be aware of? And how do I relate them to something? I am a visual person. So it's cool to think if I'm in an uncomfortable position where I'm with someone else who's white and they have just said something racist. And it's really helpful to be like, I've got Manjushri sword, it's fine. I'll just cut through what they said. And to do it in a way that is, I love you and that's not okay. That's a reverend angel practice. I love you and that's not okay.

Desiree (59:44.245)

And also, I love you and I don't need to be near you in proximity.

Kait (59:48.91)

Yeah. And then we've got Prentiss Hemphill layer of boundaries or the distance at which I can love you and me simultaneously. It's really easy in a lot of spiritual spaces and especially in Buddhist spaces for people to get very both sidesy about stuff. And I was like, no, there are lines. You have to understand the fundamental difference.

I can't remember the exact quote, but there's the James Baldwin quote, we can disagree, but if your disagreement is about my fundamental humanity, then no. When we're talking about disagreeing, we're like, “Well, I love this flower.” “Well, I just like that flower, I think it smells terrible.” I'm like, “Okay, we can disagree. But if your disagreement is, I think you're subhuman, and I think you should because your existence makes me uncomfortable because of something I'm not taking care of in myself.” An interesting thing I've learned while I've been doing my research and study around Avalokiteśvara is that every single representation of Mahākāla. So Mahakala, this amazing, wrathful deity that has the most ferocious face. Their facial hair is fire. Their eyes are wild. And they've got two, four or six arms and they're holding skull cups of brains and they're wearing human skins. Every single Mahākāla is a manifestation of Avalokiteśvara. Isn't that interesting?

Desiree (01:01:37.013)

Really? I did not know that.

Kait (01:01:39.742)

Yeah, that's the thing. They show up however they need to show up. A lot of these deities are different manifestations of each other in different forms and I think, oh wow, that's interesting. One of the most wrathful protector deities, the most like, you are accountable to doing your work, to owning your mind, is also the embodiment. So Thousand-Armed Avalokiteśvara is the embodiment of all the compassion of every Buddha.

Desiree (01:02:14.621)

I love the fluidity of that. There's a fluidity and then it just taps into, this is how I need to show up as a being right now based on what is in front of me and what it is that I need to do.

Kait (01:02:31.878)

Exactly, exactly. It's like, what is that energy behind that? Again, centering things, this is something I learned in my Buddhist chaplaincy, what's your North Star? And the North Star is what do you stand for? Because it's so easy to say like, I hate this, or I'm against that, or that's wrong, or that's bad. But what do you stand for? When I think of protector deities, may be cheesy, but in Star Wars, there's that scene right at the very end where Finn's going just kill himself and Rose saves him. And she says, “We don't win by killing what we hate, we win by protecting what we love.” And the point is he would have just died, he would just have burned up and they wouldn't have cared and would have made no difference and it would have made a massive difference to the people who loved him. So, it's that. This is why existence is resistance.

Just existing in a world that doesn't want you to be there. And I was like, that's that fierce protector. How do I show up to protect? How do I show up to protect what I love, which is the sacredness of every single precious human being?

Desiree (01:03:46.525)

Breathing that in for a moment. I was only on page one of my questions. I do want to be respectful of your time. A couple more things. Let me focus on myself.

Desiree (01:04:16.361)

We have not yet talked about embroidery and sacred loves and sacred lives. I don't know if you'd like to start by sharing about what that is or if we should start with the Punk Rakusu.

Kait (01:04:42.184)

I mean, I'll go in. Sacred love, sacred lives. A big part of my practice that I'm not very good at is remembering to include myself in all that compassion.

Desiree (01:04:59.355)

Oh yeah, I always remember Rev Angel saying once, that we need to include ourselves in our liberation work.

Kait (01:05:09.45)

Compassion for all beings. But not me, because I'm a hot mess. Sacred Love, Sacred Lives is something I started last year because I was so angry and sad. It's hard watching the people I love being attacked by bigots and conservatives who would not exist in public. It's hard knowing that like I have reached a point in my life where I'm relatively comfortable in my skin again and feel content. And also now it's scary to go out when I say, have a fresh, very short haircut. And I don't know if someone's gonna yell at me because dare I not perform gender according to their rules. It was getting upsetting and hard for me. And I was thinking about this whole protect what you love instead of always attacking what you hate.

There's like a long story I've written about it in my blog, a whole thing about listening to a podcast and someone talking about disabled love is sacred. And I was like, yeah, we're living at a time where people seem casually very comfortable with eugenics again. It's weird.

And disabled people are anywhere from 40 to 50% of the population at any given time. All of us are only temporarily able. And it doesn't suck to be disabled. It sucks to live under ableism. It doesn't suck to be black. It sucks to live under white supremacy. Doesn't suck to be queer or trans. It sucks to live under cisheteronormativity.

I started these mixed media embroidery pieces because stabbing stuff, a whole bunch is therapeutic. Let's bring my wrathful dakini energy into it. And what's fun about them is that I also then reach out to other artists whose work, like they do line drawings and their work could translate well into embroidery. I've been doing a series of them. I've decided to do 108 because Buddhist.

I'm doing a bunch of my designs and then I'll ask other artists if I can use their designs and if they give me permission to then I make the piece and then I post it back to them, which is fun because it's like spreading this joy. Right now it's just I'm just doing it for funsies. I'm just doing it to remind myself that I am a precious child of the universe. There are lots of us out there. We're all great and making art that celebrates this community that I've found so much belonging and care. And then being able to share that out with other artists, it's quite fun and it's good for my mental health.

Desiree (01:08:15.365)

And it's amazing and beautiful. I will be sharing all of that in the show notes so everyone can take a look. Maybe this is a good question around the corner towards the end here. Tell me about public dancing.

Kait (01:08:46.011)

Oh, that's a fun throwback. I've already given you my wonderful childhood story. And I was a kid, how in the 90s dance like no one's watching, was like the live-laugh-love of the time. When I was a kid, I heard that I was like, yeah, that's me. I danced like no one was watching. It's like what kid doesn't, honestly.

As an adult, I was like, it's some bullshit that people don't just dance in public. Like little kids, they'll just dance to anything and they have fun and they're not thinking about whether or not people are looking at them or not. They don't care. Or if they do, they're like, good, someone's looking at me as an audience. So, I have done public dancing at various times for different reasons. I've usually done it to promote books that I've self-published that I feel weird about now. That's a whole other story. I like doing it. I like that it charms people. I also am charmed when I see fellow public dancers.

Desiree (01:10:36.325)

No, I love it. I just wanted to mention it because I saw, one of the clips. I will tell you, you're right, charmed is the right word. But it was so joyful. And it reminded me that we so often don't encounter people allowing themselves to just be and be present and to have fun without all this extra. At least that's what came across what I saw. And it was just a gift at that moment when I saw it.

Kait (01:11:16.738)

Yeah, I would say just to add a nice little nugget on it, I think that joy is so important, and noticing joy and cultivating joy and being intentional about joyfulness. I have to share all my immense gratitude for that with Adrienne Marie Brown in her book Pleasure Activism. When I read Pleasure Activism, it helped me reframe, so I was thinking like as Buddhists, we're always like, how do we alleviate suffering? And I was like, how do we create joy? That's a more fun question. Because otherwise, it can be really easy to get heavy.

Desiree (01:11:52.405)

And it's part of the work. And is there anything else you would like to voice out into this space here that maybe we haven't touched on yet?

Kait (01:14:56.723)

I mean this is why I hate when people ask what I do because there are just so many other things. But no, I think we're good. Thank you so much for having me. This was delightful.

Desiree (01:15:07.605)

This has been amazing. I'm excited to see what unfolds from the continuing practice of the project that you're working on, and all the projects that you're working on. Not singular, multiple, complex, and all interconnected.

Kait (01:15:32.906)

Karma Ratna. That's me. Anyone who knows the five buddha families will know what I'm talking about.

Desiree (01:15:41.661)

I'll have to Google it.

Kait (01:15:45.037)

Karma, action, Ratna, abundance.

Desiree (01:15:50.005)

Amazing. And that you are living in this and you're being it. I'm thankful that you're doing all of this practice and offering it out into the world and being who you are and existing. Thank you so much. I have your bio. I think I have everything that I need now on my end.

Kait (01:16:07.47)

Thank you so much.

Follow us on Instagram at: @choosingtocreate