Episode 1

Rusia Mohiuddin

“Art is effortlessly political.”

“We need to dismantle some of the grand ways in which we think about doing social justice work, doing political work, doing artwork, when it can be a microcosm, a manifestation within ourselves to actualize a desire we have. It doesn't have to be anything more than that. If we do it for ourselves, we're doing it for the world. Because we're a part of that world.”

- Rusia Mohiuddin

Rusia Mohiuddin comes from a long line of people in her family who have committed their lives to living in service to others. Her grandfather, Mashiur “Jadu Miah” Rahman, was the father of the Bangladeshi Independence Movement, and her mother Monsura “Mukti” Mohiuddin was a former Member of Parliament who served & fought for poor people both as a historically elected official & as a citizen. In this episode, we’ll be talking with Rusia about how her family’s values and history influenced her to continue that legacy. She shares with us how approaching her organizing and social justice change work in a more mindful and contemplative way brought her back to her art making. We explore artmaking as a political and spiritual practice, and discuss how both creating art and working towards social change can be powerful acts of alignment with our values and what is most important to us.

-> See Rusia’s art, printmaking, and calligraphy on Instagram

GUEST - RUSIA MOHIUDDIN

Based in New York, Rusia is a master trainer, facilitator, coach and strategist who pioneered the integration of somatics into an organizing framework. She currently the founder and principal of UP and the founder of Ma Mukti Foundation. Her current mission, through Universal Partnership, has been developing a holistic model for social justice change work that places in its center the necessary transformation of social change agents. Rusia brings a unique style to creating pathways for individuals to bring their best selves forward when enacting social change in their organizations & communities. Rusia has also developed a model for coaching social change agents, called Embodied Coaching, that is based on her developed model of embodied leadership.

“Apa Moni” by Rusia Mohiuddin

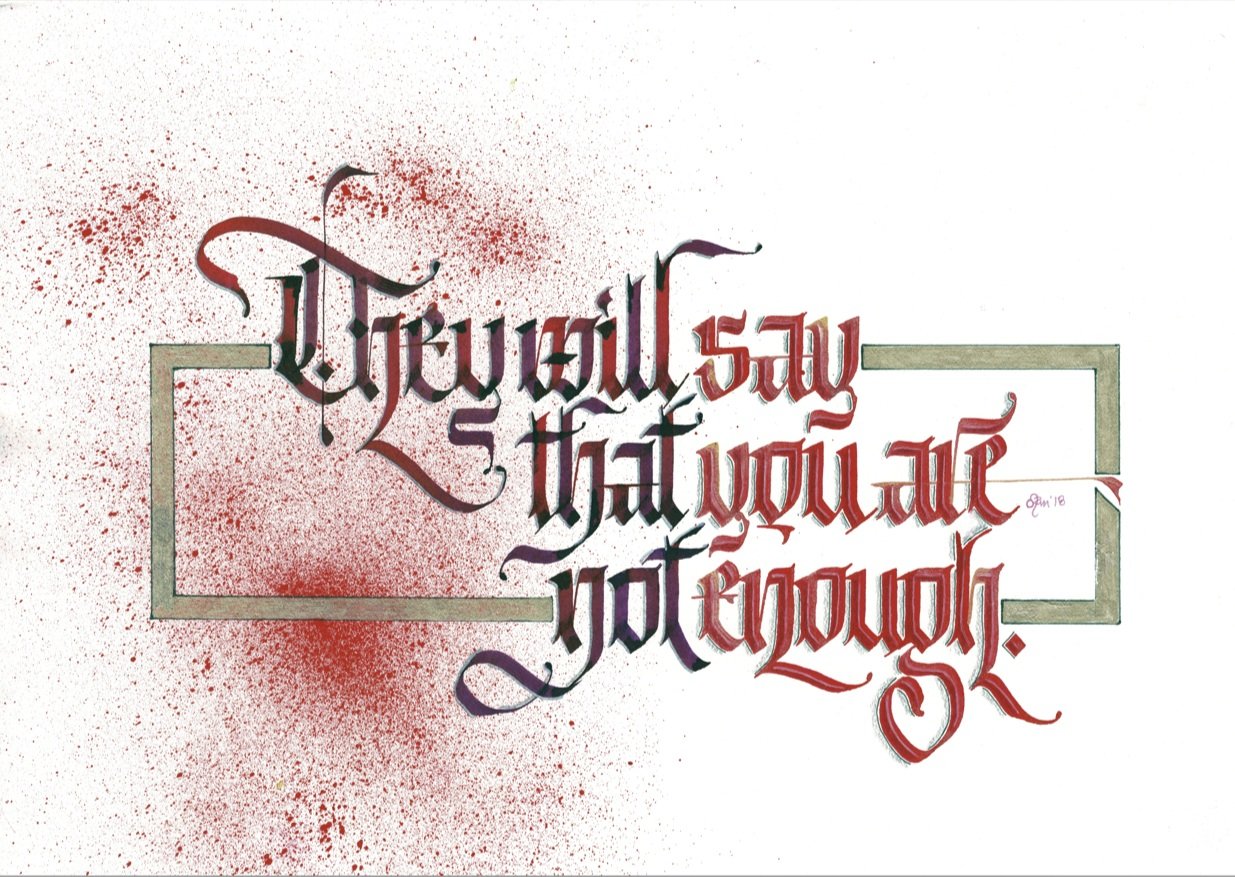

Artwork by Rusia Mohiuddin

“Liberation Tree” by Rusia Mohiuddin

-

On Spotify

On Apple Podcasts

On Google Podcasts

On Amazon Music -

Rusia Mohiuddin:

My name is Rusia Mohiuddin. I am a consultant. One part of my life is as a consultant, the principal at Universal Partnership, which is my national consulting practice. And I work with a bunch of social justice-oriented, grounded in the values of nonprofit organizations. The other half of my life is as the founder and co-director of an organization that I founded in memory of my beloved mother called Ma Mukti. Mukti was her first name and it means liberation. We launched that on her birthday this year at the end of August, August 31st.

Desiree Aspiras:

August 31st. Lots of stuff coming up this August. And related to your mom, I was reading about the foundation and so much of the work that she did and that her name means liberation. It reminded me of my maternal grandmother in the Philippines, Dolores Dulay, her name Dolores meant suffering and pain. She was a doctor to the poor her whole life. So I was reading about what you're doing with the foundation and its goal to essentially serve the poor. Is that correct?

Mohiuddin:

Well, the part that happens in this country, but then also with the aspiration of going to Bangladesh and some other developing countries to feed, clothe, and educate the poor, like people who are living in abject poverty. I think it's important to say that my mother being named Liberation Mukti is not a mistake. Her father was the founding father of the independence struggle in Bangladesh. His name was Moshiur Rahman “Jadu Miah.” His nickname was “Jadu Mia,” which meant Magic Man. It makes sense that a revolutionary that brought independence to Bangladesh before the cessation (Bangladesh was formerly East Pakistan) so it makes sense that a revolutionary would name his first child liberation. That just makes sense.

Aspiras:

A powerful name.

Mohiuddin:

Yeah, it's beautiful. My mother was a trained artist. So this feels all sorts of relevant, but she used the creativity of her teachings and her natural talents to think about how she could do politics, think about how she could serve women and poor folks living in that abject poverty. But she would gather clothing and food and wait until it was dark, like 11 o'clock, 12 o'clock, and then would go to the poor parts of Dhaka, which is the capital of Bangladesh, and other villages, because she knew that was when people were at home. And she wanted to make sure she could give it directly to the folks. She didn't do it necessarily so people could see her do it, which is when people do it in the daytime. But she wanted people to have the things. So she would feed folks, clothe folks, do all these things that she wouldn't tell anybody about. But now and then she would tell me the story as a lesson. Like you could do this too. You should do this too. She understood there was a lot of privilege living outside of Bangladesh, particularly in the United States, and that we had more than we needed. We're not like uber capitalists and materialistic, but even then we have way more than we need. And so when we were done with something, she was like, “Put it away, put it in a suitcase. There's always people going home. Bring it back to the folks because it has use. It could clothe someone, it can make someone feel warm, it can make someone feel whole. They can tap into their dignity and humanity with this thing that is no longer useful to you. It has a lot of living and has a lot of life.” So we wanted to honor some of these main things. The core part of Ma Mukti organization will be to advance the leadership of women across our movements as a real organizing campaign, really aimed at who's on the front line. Any victory, any material change that happens in the United States mainly, but all over the world, the front lines are filled with people who look like you and I. Black, brown, women. So we've developed a whole one-year leadership cohort, a summit that works to instill a certain amount of skills and qualities, bring folks together, celebrate us, celebrate our joy. All nestled under the goal, the aspiration of really advancing women of color leadership, both cultivating it on an individual level, but centering it on a collective level. We're working on some surveys, making meaning out of the data to figure out a strategy of how women and women of color specifically, take on more and more mantles of leadership across our movements. We're the ones on the front line, we make things happen and it makes sense for us to be leading our movements. And closing this, there's a great disparity between who foundations fund, and what kind of work they fund. Yet there's less than 1% of $65 billion that goes into giving that goes to women of color. It's shocking but not shocking and we're hoping to close that gap a little bit.

Aspiras:

Move the needle a little bit. As I'm listening to you share this, just this one segment of what you're working on, just hearing how some of it is inspired by honoring, paying this forward, and cultivating what you've seen as important for the next generation of women leaders. I want to circle back to your mom and you mentioned some of these things that she would share with you. How old were you? I guess I'm curious about what are some of the earliest memories of her imparting some of what she wanted to see you take up and do.

Mohiuddin:

Yeah. I'm not entirely sure my mother understood what I did, mostly because she wanted me to be a lawyer. It's a very South Asian thing. Doctor, lawyer, engineer. She wanted me to be a lawyer because her real aspiration was for me to get into politics. She was a former member of parliament, which is following her father. She wanted me to be a politician. So she would tell me at a very young age, all the things, like all the stories about my grandfather, about the work that she did. There were these political, contentious things that happened when she was born and they would tell me these stories. Eventually, she moved and lived with her paternal grandmother. That's where my mother got politicized. Because her paternal grandmother, every Saturday, she would cook all day to feed everybody in her village. So, her paternal grandmother was incredibly influential in creating this mindset, this hard set of service to human beings. And there were just a lot of smaller stories that didn't translate well in English. But she grew up in this life of service or everybody did it around her. She expected all her children to do it. So when we go do these things to continue her legacy, her four children go with her, and her two grandchildren come with us. It feels like a small thing that we could do to honor her.

Aspiras:

So your mom was a trained artist. You are clearly an artist. The artistic, the creative piece, how far back does that go?

Mohiuddin:

Yeah. As long as I can remember, I've always sketched, I've always drawn. It's usually been portraits. For as long as I can remember my existence, I've been doing it. I don't consider myself an artist. It's silly. I know. But I'm not formally trained. This is literally a gift that me and my twin sister got from my mother. My elder sister's an incredibly talented artist too. She doesn't do it as much, but this just got somehow from her womb into us. While we were in utero, we got this. Up until college, I just did art as recreation, but it was the thing that I did for recreation.

And then somewhere when I started, I just stopped. I didn't do any art for 15 years. And I just threw myself into this organizing movement work, social justice work. I don't know what happened, but something clicked. I was like, oh, I got to do something. This was the most unhealthy part of my life, where it's like 13, 14, 15-hour days. And then I just picked it up. I realized that there was this arc. You're working at an untenable pace. This false narrative, this false idea, very capitalistic, that I have to extract all this labor for myself and it's okay to do it because it's for a good cause. It's for people who are struggling. It's for our communities. And it's like, my communities, our communities don't need me to add my suffering to alleviate suffering. That just doesn't compute. So, I started to rethink how to be more mindful and contemplative in my work. And then the art just came back naturally. And it's powerful. It's powerful if you just stop to think about it, here's this thing that I did that actually is creating. And it only came back to me once I was aware of what I was doing to myself. Like getting myself into an early grave, God forbid, by working these obnoxious hours and not achieving as much as I thought I should have been in. We got a lot done. But we probably could have done it in eight-hour, nine-hour days. We didn’t have to spend the night at the office. It's absurd. But now it's like my self-care, it's my self-care practice. I use the process of creating art as my self-care practice.

Aspiras:

I know you mentioned when you started back into creating. You started with the portraits and several different kinds of illustrations. As you started to bring that back into your day, the creative practice and making art, what did you notice in terms of how that was touching on other areas of your work?

Mohiuddin:

Well, I do a lot of healing justice, transforming leadership, and aligning values. And it's all about centering one's humanity. Like, what is your relationship to yourself first? And then defining what is your relationship with others. How do you cultivate that in a way that acutely the values are aligned? And a lot of that has to do with breaking the paradigm of how everything gets commodified in the Western world, particularly in the United States. Here I am trying to train people on how to have a daily self-care practice that is about pausing. It's like a revivification process of everything that makes a human being feel alive.

And then the popularity of wellness and self-care started to kick off. And then everybody was like, oh, I haven't seen a movie in two years. #selfcare. I didn’t get my nails done. #self-care. Oh, I haven't seen my friends in 20 years. Yes, that's self-care, but it's not the kind of self-care that is taking care of the self. It's these things we do because it's joyous. It's like connecting to the vitality of what you are, who you are, and how you wanna be in the world. It's the rhythm of your energy. When you feel like you're giving it all in one thing and you feel outside the benefit of that, there's this thing that you do that reminds you that you're a part of everything. We tend to isolate ourselves when we hyper-focus on something for a long period. And the act of doing a self-care practice realigns you to like, here you are, center your humanity. Life is supposed to be about joy. Remember the kind of world that you're trying to create. Begin by creating it for yourself. The shirt you're wearing, changing you is changing the world. If we are trying to create more joy in the world, how can we rob our own lives of that joy and then still be able to do that in the world? It's a little silly.

Aspiras:

It's not silly. It's part of what we need to be doing to sustain us. And like you said, to remain aligned. So this is a near-daily practice for you? What is your rhythm with it?

Mohiuddin:

If I'm at home and not traveling or training, it is a daily practice. Even if I do like five minutes, for me it is like birthing something new into the world. Even if I take something that's written by some famous person and I rewrite my favorite part of it in my handwriting on a paper of my choice, in ink of my choice, the color of my choice, that famous thing, I'm rebirthing into the world with my flavor. That's creating. People think they have to be like these trained, beautiful, accomplished things to create beautiful art. But it's just like there is this echo inside of me that I'm releasing through my art. And it doesn't have to be my words. It doesn't have to be my art. If I am recreating it, then it is the reverberation of that echo. It comes out with my energy, with my life experiences, with the culmination of everything in that moment. And it's super subtle. I don't have to intend for it to be that way. It just is. Art requires effortlessness. I don't even have to be conscious of it. It effortlessly allows one to be in their whole self. So when I do art, it's my whole self that is there. Not fragments of it, not parts of it. Not like, oh, I'm just gonna draw from my gut today. No, it's just the culmination of everything that I am, all that I am into this one thing. And I don't have to do anything to make that true. It's like, that's it. It's intrinsically that way. And it's inherently intimate. I haven't even finished yet, but I started to do all these portraits of my family members. There's a bunch of them behind me, I don't know if you can see it.

Aspiras:

I see the bottom of the frames.

Mohiuddin:

Yeah. I started to do a lot of political portraits. Obviously, Malcolm X, because I'm a Muslim, and he was so brilliant. Audrey Lorde, Nina Simone, just as many as I could think of. I didn't realize while I was doing all these like political figures, but then I sketched my mother. I did a color portrait of my father. And here I am looking at the finer details of them. I looked at a picture, a reference, and I was like, those are my eyebrows. Those are my lips. And then I did one of my paternal grandmothers because my father's like, “Do one of my mother.” And I was like, oh my God, here's my father's. Here are all my father's things, but those are also mine. I feel like something shifted in my brain, but it probably shifted somewhere else in my body first. Every subsequent portrait I did, because my sister's close college friend's father passed and she asked me to do a portrait of her father. Then it was just like this whole made-up story of this man's life. I had never met him. I didn't know anything about him. I was doing this as a favor to my sister and her friend in a time of really great loss. I can't even articulate what I was getting from this picture, but it was like I knew this man. And all I'm doing is drawing his face in this one moment of his life, whenever it was. There were just all these stories and messages coming to me while I was drawing people's faces. It was so intimate. And I feel like I know these people and a lot of them, I don't know. My mixed media opus portrait is of my maternal grandmother, who was my favorite grandparent, and whom I love dearly. And it is the most hyperrealistic portrait I've ever done. I cried a lot during it because I miss her terribly. And I just felt so much. She passed away a while ago in 1999, but everything felt like reliving these really deep, beautiful experiences and memories of her. It took me a while to do, but it was a powerful process for me. I don't think I've ever done another portrait without feeling this intense, visceral, living the experiences of this person that I'm sketching, drawing, putting lines on, defining, coloring, giving light, dark. It is difficult to explain, which is weird because I'm on a podcast trying to explain all this stuff.

Aspiras:

No, I think what you're pointing to is that when you are engaged in the act of creating these portraits, it's a true contemplative act you are sitting with. You are paying attention to the lines, the shape, the expression of the face, what it sounds like to me, to honor it in the way that you believe it should be honored. There's a real reverence I'm feeling in how you approach the work and that you are truly being present with it. You're not just doing it to get it done. This is a full embodied practice for you.

Mohiuddin:

Yeah, totally. I think it always has been, I just haven't been aware of it. This is why I say it's inherently intimate to do portrait work and art in general. It requires one's whole self to be a part of it for the creation process. I think it's always been like that. Even since I was a little kid I have drawn the reflection of my bathroom sink for my teacher. It always has been. In the last several years, it's been something that I've been aware of. The presence of that has been something that I've been aware of. And it feels revelatory, revolutionary inside of me that I can take all these things that are quietly breathing under my skin and just release them in this art. It doesn't even have to be good. Most often, I think my art is trash

Aspiras:

Okay, I’m gonna have to more than gently challenge you on that.

Mohiuddin:

It’s like I enjoyed carving this block and I felt super meditative. Like, oh my god, I enjoyed that. So much so that I might not even want to print it. I just enjoyed carving it. And then other times, it’s like, oh, this process of printing, putting this ink on this glass and then rolling and then just the act of, it will come off this block with this ink onto this paper and what I'm doing is going to get it there. Right? And then it says something to me. It's not even words, but it's like, here it is. It's a feeling of something around the transfer of something inside of me that now is visually representative of this thing. It's like a sigh of relief. It's hard for me to articulate. I'm not doing the greatest job.

Aspiras:

No, you're doing great. Because I think about just the practice of making art a lot. I look at the research on the different benefits that it provides for your mental health and everything. But part of what I'm hearing and what you're describing in the process too that I've thought about as well is how when we sit down or stand wherever we are to make something, it's offering us so many different things. We're intentionally slowing down. We're intentionally looking. And I think for a lot of people depending on what's happening in their context, in their home and their neighborhood all the things that are happening, that it can be this one moment, it might be your only moment in the day or the week where, you have the autonomy to make these decisions. I want this to be read. I wanna carve this line this way. I wanna put the ink on this block just so and create, and as you said, birth this thing. That might be the only place for a lot of us where we have that much power and agency in what it is we want to do. As I'm saying that out loud right now, I'm realizing that's not a small thing to feel what that feels like. That sigh or that momentary sense of, I made these specific choices and this is the thing I made. As you said, whether it's an image or a quote that we are recreating in our way, weaving it into our body, it's this really powerful way to feel some of these things in our body that might ripple outward in other ways.

Mohiuddin:

Yeah. And it's what makes art so powerfully political. Period. Also effortlessly political. I don't care who's doing it. We have built a society so opposite of who we are naturally as living beings, that when we can pause and do something intentional, that is creating. Whatever it is, writing, drawing, scribbling, dancing, just the act of movement even. It is inherently political because we're not meant to do that. Sleep, eat, work. Sleep, eat, work. Sleep, eat, work. In that, you're supposed to get married and have kids. I mean all the typical American dream. It's the American dream in the United States, but it's not far from the other ways in which other societies and other countries say what is a normal, typical life. And whether we intended it to be this way or not, a lot of us are not living those kinds of typical lives. The June cleaver, whatever they call it here. Not remembering a lot of things right now. I don't know why.

Aspiras:

What was that show? Leave It to Beaver?

Mohiuddin:

Yeah, something like that. I don't know. I have two dogs. I don't have children. I have two dogs. I'm incredibly close to my family. A lot of them live here. My mother lived here before she passed. We are taking care of our father. He lives with me. So, it's like not a typical life. I'm not doing a nine-to-five job. I'm doing a job where I show up when I need to show up. I show up when others need me to show up. Then I have to find space for myself when I do this art. And so all of it is like an expression of how life is political. The art so much so, because I'm not supposed to be doing that. I'm supposed to be taking care of the kids, cooking, and cleaning. All these bullshit narratives that the society tries to shape us around. So there are some things in life, in my art that are very overtly political. And then some pieces that are just a little more subtly political. I finished this piece called The Three Brains. One of the first things I learned in my somatic certification and learning process, and was like, damn, this is really good. I was astounded when I did the first print. I'm like, how did this turn out so nice? I'm not entirely sure. Because I was thinking like, oh, I should have done three separate works. All the self-doubt around creative stuff out, around like, should I? I'm like, nah, screw it. I'm just gonna do it. Already thinking about how I could fix it before I even see it done. And it came out nice. My newest piece, which I just finished carving, is called the Liberation Tree. What are we fighting for? What are all the things that we are fighting for that allow us to be connected to the natural ways in which living beings should be connected? I think I'm gonna print that later today. I'm not entirely sure I gotta look, but it's super ready.

Aspiras:

Ooh, I'm excited to see it if you post it.

Mohiuddin:

I will. I got your ID, homie. I'll send you a print.

Aspiras:

Speaking of printmaking, where did you learn printmaking? When did that start for you?

Mohiuddin:

I didn't learn it anywhere. During the pandemic, everybody came to my house. Like, everybody come, we'll just stay here. My elder sister has the two loves of my life, my nephew and my niece. So 10 people, two dogs in a house. It's a medium-sized house. It's not large. It was incredibly intimate. I'll just leave it at that. But I bought a kit for them so we could do some art together and keep busy and whatnot, because all my gigs were canceled, and their school canceled. I was like, we gotta do something. So I just remembered that I had it. I did some with them. I enjoyed carving. It just felt very meditative to me. Like, here is this thing that I can just gently begin to work on and then when I'm done, it's something. It's like, I carve away all the things that I don't need to end with the thing that I want. Like, just think about what I just said. Carve away to end with what I want. Which is so much of what we don't do in life to take care of ourselves. Let's get rid of the excess, let's get rid of the baggage. And here I was able to do it. I started with 4X6 rubber, soft-speed ball blocks. I just taught myself by practicing it. Nobody said this. I asked Maria a few times. I'm like, help me with this negative positive space thing because this doesn't translate to black paper or white paper. And then she just talked me through it a little bit. And then I was like, it's still super confusing for me. I don't know why. It's supposed to be simple, but it's just like…

Aspiras:

It's not. Figuring out what the background's gonna be versus… it can mess with you sometimes. But I love what you just mentioned though. Because I've never thought of printmaking in that way or carving in the way that you just mentioned. It's like this practice of, what do I not want here? What am I editing? What am I letting go?

Mohiuddin:

Yeah. It's wild. I like thinking about it. I've learned in somatics from many teachers, that it's a body-based way of understanding something. And we do a lot of that. I do a lot of that in my work as a way of getting to the embodied part of what serves you right now and what will serve you for this aspirational vision that you have for yourself and your community. And here's art serving it up, serving up mad lessons. In this block, I remove the thing that is not useful for the thing that I'm trying to create. So if I can do it on a physiological level, then actualizing the letting go and carving away in my real life, whether it's intellectually, emotionally, physically, or all three, becomes achievable because I’ve already done it successfully on this block and I have muscle memory around that. I have memories inside of my body that know what it feels like to let go of things that are not a part of what I want to be, who I want to be, and where I want to go. Like I've done it on this block already. I'm not kidding when I say it's my self-care. It's like a serious, body-based exercise that allows me to take care of myself in a way that I can reconnect to the things that matter to me. How can I be a living manifestation of my values? Carve this block. Carve things in this block that aren't a part of the vision that you have for yourself, for this piece. And then I can do that. Carve away the things in my life, the ways that I practice, the pattern and ways in which I behave that aren't a part of this vision that I have for myself in the world, who and how I want to be in the world, how I want to walk the world. And it's powerful. I feel powerful just saying this out loud because most of this just existed in my head.

Aspiras:

And I am deeply listening. I don't know that I've appreciated carving as a meditative practice. I also do letterpress, setting type, and locking all of that up as a practice. Just hearing what you've shared now, it's almost a way of being a spiritual practice. It's pointing to how it's all interconnected. This is not separate from the other work that you're doing.

Mohiuddin:

Nope, not at all. Developing, achieving, understanding, and being aware of alignment is something that is a critical foundational part of my work and who I am. I don't see it separately. So anything that I do that supports me in being the best version of myself in any given moment has to be political, it has to be connected, it has to be spiritual, and it has to speak to the deeper values that I have for myself and the work that I do. So, it's all interconnected. It has to be because it's coming from me. So everything we do in some ways, whether we want to recognize it or not, is deeply connected to who we are. Because it's all coming from us. It's all coming from me.

Aspiras:

Well, it's a mic drop. We're done. That's all we need to say right there. I'm just really appreciating now how you're showing up in all of the spaces. It's not like you show up in different ways in different spaces. You're showing up as you. Not just in your art, but in your leadership work, in all of your work. Maybe as we segue to a close, just parting words or what would you say to people that might have that social conditioning of, ‘I'm not creative, I'm not talented’ or even if drawing this thread to getting engaged in social justice, people who have the thoughts swirling around, I want to step in, but I'm not creative enough or I haven't stepped into these arenas before. What would you say to them?

Mohiuddin:

Yeah, it's a great question. More likely than not, people are creating. They're just not defining it as art. And the creation process is something that is coming out from inside of them. If they have the intention of deeply understanding it for themselves, they'll see that it's political, they'll see that it's an expression of who they are. And drawing those lines is important. I think it's fine to do art for the sake of art because it's gorgeous anyway. And it will inadvertently be all the things that art is. I also think that doing something also requires beginning to think about it. Just the contemplation of wanting to do it is the desire to do it. And the voice that says, oh, I don't know if I can, I don't know that voice belongs to people. I think that's the societal shaping. That voice belongs to somebody else. Do you want to do things and not do things based on some implanted voice inside of you that tells you who you should be what you should do and what you shouldn't do? Recognizing that voice doesn't belong to you might make it easier for people to be like, yeah, I could do it, because I wanna do it. I've been thinking about doing it, whether it's art, whether it's social justice, whether it's wanting to do something slightly different in your life. Particularly in social justice work, people think it needs to be this grand gesture. But if people just begin to align who they are and how they are in the world with what they care about the most, that's social justice work. If people can change and align themselves, they are changing and aligning the world. So I think we just need to dismantle some of the grand ways in which we think about doing social justice work, doing political work, doing artwork when it can be a microcosm, a manifestation within ourselves to actualize a desire we have. It doesn't have to be anything more than that. If we do it for ourselves, we're doing it for the world. Because we're a part of that world. That's all I got, my friend.

Aspiras:

That is amazing. Thank you.

Mohiuddin:

Wisdom from my last day of being in my 40s.

Aspiras:

Yeah, people who know me have always joked. I'm like, I can't wait to be 50 because I'll know more than I do now and hopefully feel even more solid in my body. Let me thank you for joining us again.

Mohiuddin:

Thank you for having me.

Aspiras:

Thank you so much.

Follow us on Instagram at: @choosingtocreate